Dec. 21, 2010 bag checks at Braddock Rd. via @deafinthecity.

From CS:

The debate over Metro’s warrantless, suspicionless bag searches – reviled by many as a retreat from constitutional protection against unreasonable searches, but called necessary in a new world of international terrorism by others – continues to roll along. Last week, a Metro board committee took up the issue, as other reports indicated a disappointingly tepid response to the controversy by the Metro board’s new chair.Other items:

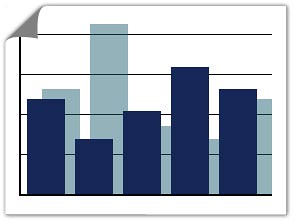

Unsuck DC Metro readers appear to overwhelmingly disagree with back checks, as the results of a recent poll suggest:What do you think of Metro's plans to institute random bag checks?Count me firmly in the majority. As others have said more cogently, the searches – ostensibly aimed at detecting explosives – are an assault on civil liberties that set the stage for even more invidious things to come. Throughout our history, police and security forces have long trampled civil liberties, in large part because police come from a command-and-control mindset, where the first instinct is to crack down or use force. (A generalization, yes, but in my experience, typically true.) And, of course, with the fear-mongering induced by politicians today, questioning security has the same pariah status as appearing soft on communism during the Cold War.

-Unfortunate, but we live in a dangerous world 23%

-Annoying safety theater 76%

Votes 3580

That said, I’d like to humbly suggest a solution that could satisfy both camps, and which I don’t think has been part of the public debate yet.

The solution starts with the understanding that the purpose of these bag checks for explosives isn’t to find explosives. This is absurd, but true. Even the cops and bag search proponents admit it. Metro police recently told the Metro Riders’ Advisory Council, for example, that they do not expect to actually find explosives during their searches. Likewise, when New York City went to court to successfully defend its bag search program – a case which WMATA relies upon heavily to justify its program – witnesses said it makes no difference that a would-be terrorist could decline a search and leave the system untouched, presumably with bomb in hand (or trench coat, as the case may be).

What, then, are searches for explosives meant to accomplish, if not find explosives?

The key, according to police and others, is that they represent a break in routine; they introduce unpredictability and uncertainty. In the New York federal court case, for instance, experts’ testimony established that “terrorists ‘place a premium’ on success. Accordingly, they seek out targets that are predictable and vulnerable – traits they ascertain through surveillance and a careful assessment of existing security measures.” Bag searching, which can be held anywhere on any given day, “deters a terrorist attack because it introduces the variable of an unplanned checkpoint inspection and thus ‘throws uncertainty into every aspect of terrorist operations – from planning to implementation.’ ”

So there it is – the key isn’t to look for bombs per se, but rather to generate the uncertainty and unpredictability that thwart the terrorists.

And therein lies the solution.

Why couldn’t Metro use some other uncertainty-creating activity, rather than faux bomb searching, to introduce that uncertainty, and which also happens not to raise concerns about busting civil liberties? Instead of pulling passengers over and violating their rights against unreasonable searches by looking for explosives they don’t really expect to find, how about, say, beefing up platform patrols? Becoming highly visible in a way that’s not done now? Using additional dog patrols? Officers actually riding in subway cars enough that riders see them more than once or twice a year? (That really WOULD be unusual.) Descending into the bowels of Metro Center often enough to observe what really goes on there? And so on.

And that leads to the real beauty of such a plan – in addition to creating that unpredictability, the stepped-up activity can at the same time address other pressing needs, too. Pretty much any rider will tell you that Metro police need to be more visible and effective, whether in dealing with the hooligans at Gallery Place/Chinatown, the rowdy kids that flood the system when school lets out, or the thieves who steal iPods and iPads.

The point is: There’s plenty of high visibility, routine-disrupting activities Metro could undertake to satisfy the twin goals of 1) thwarting terrorists without stomping on civil liberties, while 2) also furthering workaday security and safety.

Given the way cops think, I doubt they’ll ever suggest something like this themselves. And Metro’s new czar/chief executive, Richard Sarles, is probably too vested in supporting the current program to back away from it now.

That leaves the Metro board. With recent changes in membership, there’s some hope for life in what has been a distressingly moribund group. But taking on the security apparatus will require guts. And unfortunately, few would accuse the board of having much fortitude in recent times. Here’s hoping a majority of the board will find spines and implement a truly reasonable solution.

SHORT TAKE: As long as we’re talking about Metro bag searches, it’s important to clear up a misconception. Metro police and others have said the program is patterned after the New York City search program, the constitutionality of which a federal appeals court has upheld.

But in important ways, the Metro program is not like the NYC operation. In approving the New York program, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals laid out several factors indicating why the program there was acceptable. Among them:

- That police exercise no discretion in selecting whom to search, but rather employ a formula. The Metro program, however, plainly does involve discretion. Even though it uses a formula – every sixth person, every 14th, etc. – passengers often arrive simultaneously at Metro’s wide station entrances and concourses (which are very much unlike the New York system). In such instances, Metro police told the Riders’ Advisory Council, when applying their formula, they will make a judgment about who “breaks the plane” of the station first. (There’s a bad football joke here somewhere.) Likewise, police said they won’t search purses, and will only search bags judged capable of holding explosives. But when does a purse become a bag? A backpack? For that matter, what is the minimum size of a bag for holding a bomb? Such things are left to officers’ discretion.

- That a typical search lasts only a matter of seconds. In the case relied upon by the appeals court, which involved road checkpoints, the time in which police had contact with motorists “lasted only a few seconds.” Yet with Metro, according to the agency’s own videos, the length of contact is considerably longer, running up to a minute.

WMATA subsidy use called illegal (WaPo)

Audit of Dulles rail requested (WaPo)

DC nightlife establishment fighting early closing (Examiner)

GOP kills Dem. amendment to restore WMATA funding (TBD)

Oct. 11, 2012

Oct. 11, 2012 February 21, 2012

February 21, 2012 March 4, 2010

March 4, 2010